Language is the roadmap of a culture.

It tells you where its people came from and

where they are going.

Rita

Mae Brown

ORIGINS OF ARMENIAN LANGUAGE

Determining the origins of a language requires

a paradigm and framework. The paradigm in the

case of the Armenian language is the assumption

that it belongs to a family of over 100

languages, collectively described as

Indo-European

that share the same origin. The framework for

this assumption is the analysis of the words

and the sounds of the languages that share an

Indo-European heritage. The study of a language

to determine its origins and evolution deals

primarily with its oral characteristics, and

most contemporary linguists work under the

belief that spoken language is more

fundamental, and thus more important to study

than written language.Thus, Armenian is

considered to be mainly an offshoot of the

Indo-Hittite group of languages. The consensus

among linguists who accept the affiliation of

the Armenian Language with the other languages

of the Indo-European family is that it

constitutes an independent branch within the

group.

In his later years Hübschmann, almost exclusively, continued his research on the Armenian language and authored several books on the subject. More recent linguists and experts on the Indo-European languages solidified Hübschmann’s conclusions and further enhanced the research. The Swiss linguist Robert Godel and some of the most prominent linguists or specialists on Indo-European studies (Emile Benveniste, Antoine Meillet and George Dumezil) have also written extensively on different aspects of Armenian etymology and its Indo-European heritage.

Not surprisingly, other theories about the origins of the Armenian language have also been suggested. In a sharp departure from the Indo-European theory, Nikolai Marr advanced the theory of “Japhetic” origins and, based on certain phonetic characteristics of Armenian, together with the Georgian, derived from one common language family, called Japhetic and related to the Semitic family of languages.

In addition to the dubious theory of Persian origins, Armenian language is often characterized as being closest to Greek. Yet, neither of these attributions, the result of often borrowed information, is seriously validated from a purely philological perspective. The Armenian philologist Hratchia Adjarian has compiled an etymological dictionary of Armenian which compilation contains 11,000 entries of Armenian root words. Of these, the Indo-European component is only 8-9%, loan-words constituting 36% and an overwhelming number of “undetermined” or “uncertain” root words that constitutes more than half the vocabulary.

Within this context, Armenian, with an uninterrupted evolution through time and geographical space, continued to evolve and be enriched by neighboring cultures, as attested by the loan words, and, after the alphabetization of the languages, to be further enhanced by exchanges with distant cultures. Consequently, it is safe to assume that the Armenian language in its current expression has a history of approximately 6000 years.

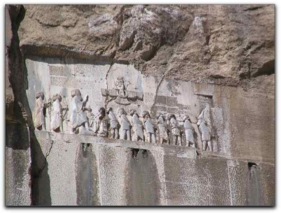

If the linguists who prepared the Behistun texts in 520 BC equated Armenia and Urartu as an interchangeable designation for the same land, and given the antiquity of Urartu, this may provide linguistic evidence for an additional…1000 years of Armenian civilization and culture.