EVOLUTION OF ARMENIAN

LANGUAGE

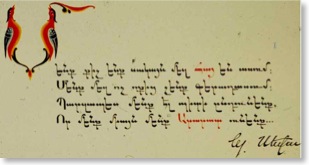

In the period that followed the invention of the alphabet and up to the threshold of the modern era, Krapar (Classical Armenian) lived on. An effort to modernize the language in Greater Armenia and the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia (11-14th centuries) resulted in the addition of two more characters to the alphabet, bringing the total number to 38.

The Treaty of Kermanchai of 1828 once again divided the traditional Armenian homeland. This time, two thirds of historical Armenia fell under Ottoman control, while the remaining territories were divided between the Russian and Persian empires. The antagonistic relationship between the Russian and Ottoman Empires led to creation of two separate and different environments under which Armenians lived and suffered. Halfway through the 19th century, two important concentrations of Armenian communities were constituted.

The introduction of new literary forms and styles, as well as many new ideas sweeping Europe reached Armenians living in both regions. This created an ever-growing need to elevate the vulgar language, Ashkharhabar, to the dignity of a modern literary language, in contrast to the now-anachronistic Krapar. Numerous dialects developed in the traditional Armenian regions, which, different as they were, had certain morphological and phonetic features in common. On the basis of these features two major variants emerged:

Western Variant: The influx of immigrants from different parts of the traditional Armenian homeland to Constantinople crystallized the common elements of the regional dialects, paving the way to a style of writing that required a shorter and more flexible learning curve than Krapar.

Eastern Variant: The dialect of the Ararat plateau provided the primary elements of Eastern Armenian, centered in Tiflis (Tiblissi, Georgia). Similar to the Western Armenian variant, the Modern Eastern was in many ways more practical and accessible to the masses than Krapar.

After the First World War, the existence of the two modern versions of the same language was sanctioned even more clearly. The Soviet Republic of Armenia (1920-1990) used Eastern Armenian as its official language, while the Diaspora created after the Genocide of 1915 carried with it the only thing survivors still possessed: its mother tongue, Western Armenian.

To appreciate the cultural-linguistic importance of Western Armenian requires an understanding of the historical imperatives at play: For years now, particularly with a new generation of Armenians in America raised without the opportunity to learn the language, Armenian identity for many began and ended with the Turkish genocide of 1915, the genocide that spawned the birth of Armenian dispersion. Armenian identity, politics, religious beliefs and world vision have been dominated by this terrible event.

The historic aim in the Diaspora has been to re-convince the world of the truth of a single event--in order to establish a past that can explain the present Armenian condition.

For Armenians living in the Diaspora, in

addition to defending the historical record,

preserving the linguistic and literary heritage

is an important part of the struggle.

Language is the inventory of human existence.

L.

W. Lockhart