MORPHOLOGY OF ARMENIAN

LANGUAGE

In general, the morphology (syntax

or

linguistic typology)

of a language is similar to a road map. Syntax

and Linguistic Typology provide the basis of

the combinatory behavior of words that are

governed to a first approximation by

their

part of speech

(nouns, verbs, adjectives, etc.), a

categorization that goes back to the tradition

of the Greek grammarian Dionysios of Thrax

whose works were already well known in the

Armenian highland as of first century BC.

This overview is intended as an introduction in

order to underline the particularities of the

language and highlight the importance of the

inflections in Armenian grammar (declension of

the nouns, conjugation of the verbs, etc.).

A. Syntax

In linguistics,

Syntax

(Greek,

syn,

with +

taxis,

arrangement) is the part of grammar which deals

with the order, arrangement, and the relations

of the words in a sentence or a phrase.

Although modern linguistic research into

natural syntax attempts to systematize

descriptive grammar, Armenian syntax defies the

many theories (theories that have in time risen

or fallen in influence) of

formal syntax.

A modern approach to combining accurate

descriptions of the grammatical patterns of a

language with their function in context is that

of

systemic functional

grammar,

an approach originally developed by Michael

A.K. Halliday in the 1960s and now pursued

actively by linguists on all continents.

"Colorless

green ideas sleep

furiously"

is a phrase composed by Noam Chomsky in 1957 as

an example of a sentence that is grammatically

correct in terms of

syntax

but whose meaning is nonsensical. However, this

phrase was used by Chomsky to demonstrate the

inadequacy of the then-popular probabilistic

models of grammar, and the need for more

structured models.

We can almost state with a certain degree of

certitude that Armenian language is not

concerned with the grammatical debate on Syntax

or the formulation of the different theories on

the subject since the well structured

inflections of the words in Armenian grammar

provide a flexibility that endows the language

with a depth of expression that is not

restrained by the grammatical rules or

principles of syntax and the variations in an

Armenian phrase are often a matter of emphasis

on one of the elements in a phrase (i.e., the

action/verb, the subject of the verb or its

object) or style of writing rather than a

grammatical imperative.

Although it is tempting to use the phrase by

Chomsky "Colorless

green ideas sleep

furiously"

as an example to underline the flexibility of

an Armenian phrase, it may be more appropriate

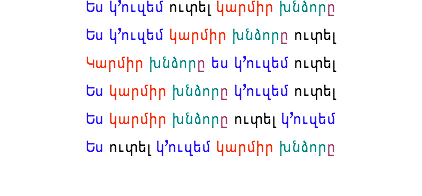

perhaps to use a common and “sensical” phrase:

I want

to eat

the

red

apple

Without the addition of any other words to the

English language phrase, there is only one

grammatically accurate way to express the

desire of wanting to eat a red apple. Yet, if

one is to assign the task of translating this

expression into a grammatically correct

Armenian, we may end up having the following

choices:

It has to be noted that all the expressions in

the Armenian sentences are grammatically

accurate and no poetic license is applied in

their composition. Obviously, there are perfect

grammatical explanations to elucidate the

flexibility of the Armenian syntax. To cite

just a few:

1- The distinctive ending of each case of the

conjugation of the verbs in Armenian allows the

separation of the stem of the verb from the

subject and the insertion of other parts of the

components of the phrase between the

subject

and the

verb.

while it is not possible to do so in English.

2- The

Accusative

case of the word

apple

offers the possibility of placing this word

almost anywhere in the phrase since the

case of the declension

clearly defines the role of the word as the

object of the verb.

3- It is also possible to reverse the order

of

I want to eat

(I to eat want) in Armenian since there is no

grammatical obstacle to do so. The permutation

of the conjugated part of the verbs (I want)

and the infinite form (to eat) are not

restrained by any rule of syntax or grammar.

B. Typology of Armenian

Phrases:

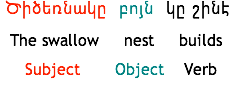

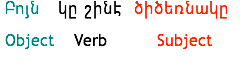

Armenian is considered an SOV type language. In

other words,

Subject-Object-Verb

(SOV) is the type of languages in which

the

subject,

object,

and

verb

of a sentence appear (usually) in that order:

If English were SOV, then "The swallow nest

builds" would be an ordinary sentence. However,

there is nothing dogmatic about this rule. It

is also accurate to reformulate this sentence

and write:

Yet, it is accurate to state that Armenian is

SOV type language since this type of languages

have also other characteristics that

distinguish them from members of other

families:

1- SOV languages have a strong tendency to

use

postpositions

rather than prepositions.

2-

To place

genitive nouns*

before the possessed noun:

3-

Within Eurasian SOV languages, adjectives are

often placed before the nouns they modify:

C.

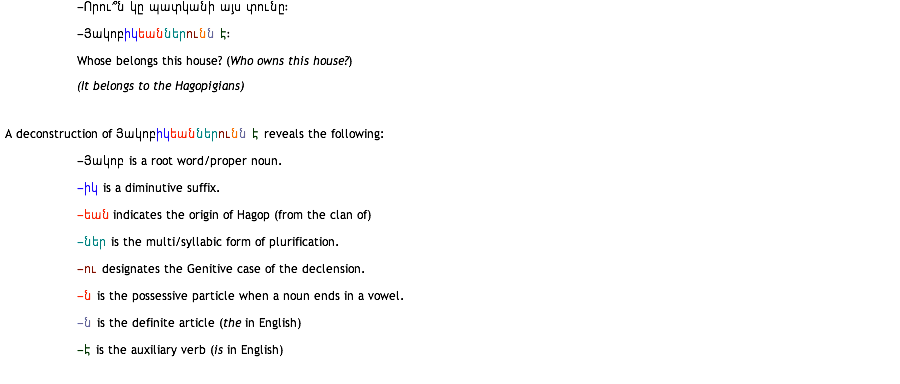

Agglutination:

An

agglutinative language

is a language in which derivative words are

formed by joining morphemes together. This term

was introduced by W. von Humboldt in 1836 to

classify languages from a morphological point

of view. The word agglutinative is derived from

the Latin verb

agglutinare,

which means "to

glue together."

An agglutinative language is a form of language

where each affix (prefix or suffix) typically

represents one unit of meaning (such as

"diminutive," "past tense," "plural," etc.),

and bound morphemes are expressed by affixes

(and not by internal changes of the root of the

word, or changes in stress or tone). Besides,

and most importantly, in an agglutinative

language affixes do not become fused with

others, and do not change form conditioned by

others.

Agglutinative languages tend to have a high

rate of affixes/morphemes per word, and to be

very regular. For example, Japanese has only

three irregular verbs (and not

very

irregular), Nahuatl only two. Armenian is an

exception; not only because it is highly

agglutinative (there can be simultaneously up

to 8 morphemes per word), but there are also a

significant number of irregular verbs, varying

in degrees of irregularity.

An example of an agglutinative word can be the

following dialogue:

* * * * * * *

After reviewing some of the morphological

basics of Armenian grammar, it is perhaps

important to note that none of the

characteristics described above bear any hints

of influence from Classical Greek or Old

Persian grammar. Amazingly, these

characteristics reflect many of the features of

the extinct languages that were spoken within

the region, until recently known as the

Armenian Plateau (currently designated as

Anatolia) and its immediate surroundings.

The

Hurro-Urartian languages

(circa 2000-580 BC) were agglutinative

languages, but they definitely did not belong

to the Semitic or Indo-European language

families. Scholars such as I.M. Diakanoff and

Segei Starostin see affinities between

Hurro-Urartian and the Northern Caucasian

languages, yet, there is little evidence for a

relationship of Hurro-Urartian to other

language families and this view, prudently, is

not shared by serious linguists who consider

Hurro-Urartian as an independent family at

present.

Today, studies demonstrate that there is

evidence of a strong Hurrian cultural and

linguistic influence on

Hittite

in ancient times. Consequently, one can easily

conclude that together with

Summerian, Elamite, Hattic

or

Urartian

languages, Armenian grammar inherited some its

grammatical and lexical elements from the

languages that have seen their political and

military rise and fall throughout the ages.

Astoundingly, Armenian language seems to be the

only survivor as well as the only link to these

extinct languages and civilizations.