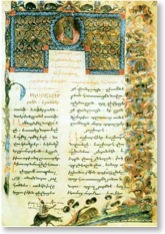

LANGUAGE AND THE LITERATURE IN THE CLASSICAL

PERIOD

Paradoxically,

the invention of the Armenian Alphabet and the

precise details of this major cultural event

eclipse the notion of the “beginning”

of Armenian language and literature.

It is perhaps appropriate to note that the recent past of the Armenian cultural and literary evolution provides a parallel and a point of reference of how a writing style cannot be created overnight. During the final stages of the transitional period (circa 1800) from Classical Armenian (Krapar) into Modern Armenian (Ashkharhapar), it took over a century to crystallize the full development of Modern Armenian in spite of the fact that the number of scholars and/or intellectuals involved in the transitional process was by far superior to the number of linguists in fifth century Armenia, as well as the relatively superior paraphernalia of spreading a language (rate of literacy amongst the population, printing presses, newspapers, etc.). In terms of literary style and linguistic clarity one has only compare the literary output created in the early 19th century to works published at the turn of the same century to realize the gradual evolution in terms of style and development of Modern Armenian. Yet, at the beginning of 5th century, the sophistication of the writing and style of the composition that emerged immediately following the invention and implementation of the Armenian alphabet more than suggests the presence of a highly developed writing style and tradition.

Today, we consider historiography and literature to be primarily secular. In fifth century Armenia, however, the adoption of Christianity was the primary source, motivation and imperative for literature. The conversion of the Armenian nation had to be fully achieved in preparation for the second coming of Christ, which was widely believed to be imminent by early Christians. While the primary task was the teaching of the new religion, the biggest obstacle to the salvation of the nation was a deeply rooted pagan past. The aggressive promulgation of Christianity demanded the erasure of that past, and such an endeavor necessitated the destruction of its records--tablets and texts as well as temples and architectural monuments.

It is often asserted that the oral tradition, that of the Kousans, the itinerant troubadours or bards, salvaged a few fragments of the collective memory from the Pre-Christian era. Stories of the triumph of Haig over Bel, of the god Vahakn and the struggles of Ara the Handsome against Shamiram are only a fragment of these stories. It is sometimes stated that there is no written record of pre-Christian literature in Armenia. Yet, this assumption underestimates the determination of the Armenian spiritual as well as political leadership to eradicate the non-Christian past. Sahag, the Catholigos, and Mesrob, the undisputed leader and inspiration of the movement to accelerate the transition from paganism past and present to Christianity, took an active part in deciding the course of action and decided the agenda by dictating the subjects of studies and the texts to be translated. It is reasonable to believe that this movement also included a methodical destruction of all written material that was deemed detrimental to the spiritual transformation.

It has to be noted that the oral transmission of literary works throughout the centuries is not, of course, unique to Armenian. The entire poetry of Arabic literature known as the Age of Ignorance (predating Islam) was recorded many centuries after the Arab world had converted to Islam, and virtually all Homeric scholars accept the oral precursors of the Iliad and the Odyssey.

Interestingly, in spite of an existing written culture that was largely made possible by the invention of the Armenian alphabet, in the following centuries, the oral tradition in Armenian literature continued to exist. A more recent example of this tradition may be the epic tale of Sasna Dzrer--Daredevils of Sassoun-- which had originated in the 10th century but was put in writing only in the second half of the 19th century.

Language is a process of free creation; its

laws and principles are fixed, but the manner

in which the principles of generation are used

is free and infinitely varied. Even the

interpretation and uses of words involves a

process of free creation.

Noam

Chomsky